‘I was a Premier League winner but I didn’t want to leave the house’

Connor Bennett

BBC News, Cambridgeshire

Reporting fromCambridge

Steve Hubbard/BBC

Steve Hubbard/BBC

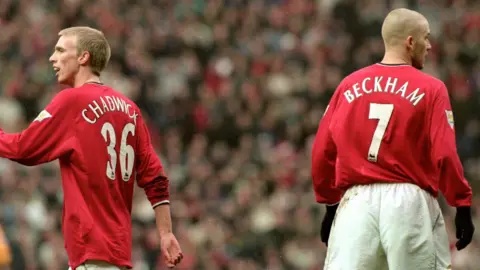

Luke Chadwick hit the heights when he won the Premier League with Manchester United, but off the pitch he was plagued by anxiety and depression.

As a young player, he suffered abuse and bullying over his appearance that sometimes left him reluctant to leave the house.

“As a 19-, 20-year-old it should have been the best time of my life but for a period of time… I didn’t want to go to the shops, I didn’t want to go out with my friends… I would just want to stay at home because I was so scared that people would talk about the way that I looked,” he says.

Now 44, the Cambridge-born player has written an autobiography entitled Not Just a Pretty Face that details the highs and lows of his career.

Chadwick won the Premier League with United in 2001, playing alongside the likes of David Beckham, Gary Neville and Roy Keane.

Getty Images

Getty Images

His career had started when he was scouted by United, aged 14.

After an impressive trial, manager Sir Alex Ferguson made a phone call to his mother, requesting he sign.

Chadwick, who grew up in Meldreth, Cambridgeshire, was just 18 when he made his senior debut during the 1999-2000 season, after two years in the academy.

Chadwick admits he went into professional football “naively”, assuming it was how he played that was important, yet soon found himself ridiculed and abused about his looks.

He was the butt of jokes on BBC TV show They Think It’s All Over, for which host Nick Hancock – and panellist Gary Lineker – have since apologised.

Getty Images

Getty Images

It was not a problem on the pitch itself. “Football was always the place I felt free; the place where I didn’t think about anything else,” he says.

“I think it was away from the game that it affected me more, and it was something that I became obsessed by internally, and I didn’t like leaving the house because, in my mind, I would just be abused or teased about the way I looked when, in reality, that wouldn’t be the case.”

- A list of organisations in the UK offering support and information with some of the issues in this story is available at BBC Action Line

As a young player, Chadwick says, he did not have the “emotional intelligence” to deal with it.

“My thoughts were to be vulnerable was to be weak – ‘I can’t show any sign of weakness’ – when, in reality, our vulnerability is our biggest strength,” he says.

“I wasn’t able to speak about it to anyone – not even my family, my friends – it was something that I kept so deep inside… and probably felt helpless, in a way, because I just didn’t know how to deal with it… and I just wanted it to stop, really.

“It wasn’t until I came away from Manchester United, and the spotlight’s not on you as much… that I was able to rebuild my confidence and live a really happy life.”

He says he was fortunate to have a loving family and girlfriend – now his wife – to help him do that.

Getty Images/AMA/Corbis

Getty Images/AMA/Corbis

Despite the medals he won there, the attacking midfielder was not a regular starter during his time at Old Trafford, making 38 appearances and scoring twice.

“I think the reason I didn’t have a glittering career at Manchester United wasn’t because of the abuse that I suffered,” he says.

“It was because I wasn’t able to stay at the high level – I suffered with a few injuries and was never able to play at the highest level.”

He left United in 2004, joining West Ham. Later he would make 246 appearances for MK Dons, as well as having spells with Norwich City, Burnley and Stoke City.

He finished his professional career with Cambridge United, his boyhood club.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Getty Images

Getty Images

Chadwick now works for a company that organises fun football events for children and encourages them into the sport.

He also works as an adviser for young professional footballers in the men’s and women’s game.

He says that while social media has brought players and fans closer together, it has also helped to facilitate “absolutely disgusting” abuse of players.

“You do feel more needs to be done by the social media channels to police that; to stop that happening,” he says.

“But I think, as a society, we are more aware of mental health on a deeper level and people are more able now to open up about their problems and deal with them in a much more positive way than I dealt with mine, many, many years ago now.”

Getty Images

Getty Images

Steve Hubbard/BBC

Steve Hubbard/BBC

And he stresses that, for all its challenges, he feels fortunate to have played at such a high level.

“I hope people that read the book or hear me speak realise how grateful I am that I had the opportunity to do what millions and millions of people would love to do, of having a career in professional football,” he says.