Just Stop Oil was policed to extinction – now the movement has gone deeper underground

Justin Rowlatt

Climate Editor

BBC

BBC

Listen to Justin read this article

Just Stop Oil (JSO) activists are dusting down their placards, digging out their infamous fluorescent orange vests, and charging up their loud hailers — a routine they have gone through many a time before.

It has taken just three years of throwing soup, spraying corn-starch paint and blocking roads – lots and lots of roads – for the troop of climate activists to become one of the country’s most reviled campaigning organisations.

They expect hundreds of activists to turn out on Saturday in Central London.

However, despite appearances, this JSO gathering is going to be very different from what has gone before. For a start it’s existence is no secret. And secondly, there is unlikely to be any of the mass disruption that has been seen previously.

In fact, this is their last ever protest. JSO are, in their own words, “hanging up the hi-viz” and ending their campaign of civil disobedience.

The group’s official line is that they’ve won their battle because their demand that there should be no new oil and gas licences is now government policy. But privately members of JSO admit tough new powers brought in to police disruptive protests have made it almost impossible for groups like it to operate.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Sarah Lunnon, co-founder of JSO, says Saturday’s gathering will be a “joyful celebration”.

“We’ve done incredible things together, trusted each other with so much,” she says.

The group aren’t the only ones who’ll be celebrating. Many of the thousands of motorists who’ve been delayed, art lovers appalled by the attacks on great paintings, or the sports fans and theatre goers whose events were interrupted, will be glad to see the back of them. So too the police. Policing JSO protests has soaked up thousands of hours of officer time and cost millions. In 2023 the Met Police said the group’s protests cost almost £20m.

But the end of JSO also raises some big questions, including if this is really the end of disruptive climate protest in the UK or whether being forced underground could spawn new, even more disruptive or chaotic climate action. And there’s a bigger strategic question. Despite widespread public concern about the future of the planet, much of the public ended up hostile to JSO. How can the climate movement avoid a repeat of that?

JSO’s model involved small groups of committed activists undertaking targeted actions designed to cause maximum disruption or public outrage. But it had strict internal rules. The actions had to be non-violent, and activists had to be held accountable – they had to wait around to get arrested.

For leaders like Roger Hallam, who was originally jailed for five years for plotting to disrupt traffic on the M25, being seen to be punished was a key part of the publicity.

The police, roused by public anger and hostile media coverage, demanded more powers to stop the “eco-loons”, as the Sun newspaper dubbed them, and other protesters. And politicians heeded the call.

Getty Images

Getty Images

The biggest change came with the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act in 2022. It made “intentionally or recklessly causing public nuisance” a statutory offence. A list of loosely defined actions including causing “serious distress, serious annoyance, serious inconvenience or serious loss of amenity” were now potentially serious crimes. And that opened up another legal route for the authorities: the charge of conspiracy to intentionally cause public nuisance. Now even planning a potentially disruptive action could bring substantial jail time.

The Public Order Act the following year broadened the police’s powers to manage protests and brought in new criminal offences including “locking on” to objects, causing serious disruption by tunnelling, and interfering with major infrastructure.

At the same time judges, backed by the higher courts, have removed the right of protestors to claim they had a “lawful excuse” for their actions in the vast majority of protest cases. The Court of Appeal has accepted that the “beliefs and motivation” of a defendant are too remote to constitute lawful excuse for causing damage to a property. It means they can no longer argue to juries that their right to splash paint on buildings, sit in the road, or undertake other disruptive activities, is justified by the bigger threat posed by climate change. In most trials the only question for the court now is whether the defendants did what they are accused of, not why they did it.

Getty Images

Getty Images

“We’ve seen people being found guilty and sent to prison for years,” says JSO’s Sarah Lunnon.

David Spencer, a former police officer who now is head of crime and justice at the think tank Policy Exchange, says too often the law had previously “favoured those involved in disruptive protests at the expense of the legitimate interests of other people.”

The human rights organisation Liberty sees things very differently, believing the changes amount to an attack on democracy.

Ruth Ehrlich, head of policy and campaigns at the organisation argues the legal changes have “had a chilling effect on the ways all of us are able to speak out for what we believe”.

What comes next?

In this context, some climate activists have concluded that it is time to drop the movement’s long-standing commitment to accountability – they will undertake disruptive actions but won’t stick around to be arrested any more.

Over the past year a group called Shut the System (STS) has carried out a series of criminal attacks on the offices of finance and insurance companies: smashing windows, daubing paint, supergluing locks, and in January this year they targeted fibre optic communication cables.

I spoke to one of the organisers on a messaging app. They argue the legal changes mean the traditional forms of accountable protest aren’t viable anymore.

“It would be impossible for people to sustain an effective campaign with people going to prison for years after a single action,” the spokesperson told me. “Activists are forced into a position where we have to go underground.”

Getty Images

Getty Images

I asked the group what they would say to people who criticise them for breaking the law. They said that in their view the stakes are such that they have to do what they think works.

This is not the first time protestors in the UK have taken clandestine action on climate issues. Over the past few years a group calling itself the Tyre Extinguishers has deflated tyres on sports utility vehicles (SUVs) in several locations, while this year another group drilled holes in the tyres of cars at a Land Rover dealership in Cornwall.

The idea of protesters causing JSO levels of disruption – but unlike JSO, avoiding justice – may send a chill down the spine of many motorists. But Dr Graeme Hayes, reader in Political Sociology at Aston University, thinks only a tiny minority of climate campaigners are likely to get involved in such actions.

He has studied environmental protest groups in the UK for decades and says the more radical groups are finding it increasingly hard to recruit people.

“There is a very strong, profound ethical commitment to being non-violent within the climate movement so I think whatever it does will be based on those principles,” he says.

‘Disgruntled people find each other’

Others have found legal ways to make their protests heard. A group called the Citizen’s Arrest Network (CAN) is attempting to flip the script by using the law of public nuisance – implemented so effectively against the disruptive protests of JSO – against the bosses of fossil fuel and other polluting companies.

The group exploits the right, dating back to medieval England, that allows citizens to arrest people they think have committed a crime. CAN put together alleged criminal cases against those company bosses they argue are causing public nuisance by damaging the environment. Then they “arrest” them in public, which involves handing them documents detailing the alleged crimes they are responsible for.

The group claims to have “arrested” a number of executives from fossil fuel and water companies and last month served indictments against Shell and BP to the Crown Prosecution Service. Gail Lynch, one of the organisers, says the group was born out of frustration, “disgruntled people find each other, and they need a mechanism to have their voice heard,” she says.

Drawing the line

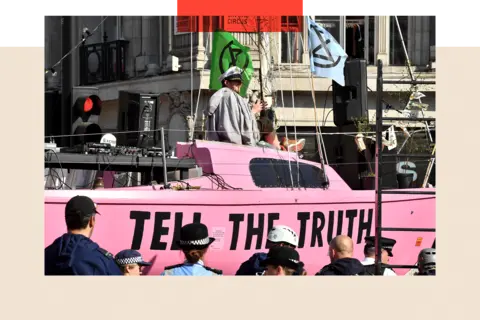

These days very few elected politicians speak out in favour of JSO’s actions. Yet as recently as April 2019 Extinction Rebellion (XR) staged 10 days of protests across the UK that caused widespread disruption and included blocking Oxford Circus in central London with a large pink boat. Instead of lengthy prison sentences for those involved, the protest leaders were instead rewarded with a meeting with Conservative government ministers.

Within two months the UK parliament had passed a law committing the country to bringing all greenhouse gas emissions to net zero by 2050. Robert Jenrick, then a Treasury minister, was one of the ministers who met XR and was still in post when the Net Zero laws were passed.

Getty Images

Getty Images

But things are different now and Jenrick, who is now shadow Justice Secretary, is very critical of JSO’s actions.

“It was completely unacceptable that ambulances were being blocked and millions of commuters were being subjected to hours of delays and misery,” he tells me.

“Just Stop Oil’s zealotry has probably set back their cause by alienating the law-abiding majority.”

Getty Images

Getty Images

Polling evidence suggests there is still strong support for climate action amongst the public.

Ahead of the general election last year, the polling organisation More in Common, along with climate think tank ESG, found around 80% of Britons thought it was important that the government cares about tackling climate change. This broad sentiment was echoed across the political board – nearly four out of five Conservative voters and two thirds of Reform voters felt this way.

But despite this, JSO is not well regarded by the public. A 2023 YouGov poll of almost 4,000 people found just 17% had a favourable view of the group.

According to Dr Hayes, what happened with JSO has prompted deep reflection within the climate movement about its future strategy.

There are some within the green movement who will be pleased to see the end of JSO.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Rupert Read, a former spokesperson for XR is one of many who believes JSO’s message on the urgency of action on climate change got lost in the outrage caused by their disruptive campaigning.

“Just Stop Oil has been effective at getting attention,” says Read, “but that’s not the same thing as getting real change.” They generated a lot of headlines: “[but] sometimes people give you coverage precisely because they think that coverage will be bad for you and your cause.”

John Gummer, now Lord Deben, was an environment minister under Margaret Thatcher and chaired the government’s watchdog on climate change for a decade. He has been very critical of successive governments’ lack of action on climate change.

But Lord Deben believes the disruptive actions of groups like JSO are counterproductive. “I think it annoys people more than it encourages people to think seriously about the issue,” he says.

His advice to people who want to see more action on climate change is to use the democratic system more effectively, for example by telling MPs and local councillors about concerns.

Public support

XR’s former spokesperson, Mr Read, believes campaigners should now focus on building a mass movement. “If we are going to actually win on this, we need to do something that will bring most people with us because there is no way one gets to win on climate without bringing most people with one,” he says.

He’s working with the former head of the Green Party, Caroline Lucas, on a new organisation, the Climate Majority Project. It lists prominent Conservatives including Lord Deben among its supporters and aims to use non-disruptive methods. The focus will be building support for climate action by focusing on tackling the impacts of extreme weather in local communities.

“The end game is that we get a situation where the political parties are racing to compete for votes on climate and nature, rather than running away from them,” explains Read.

Naturalist and presenter Chris Packham believes “empowering” voters should be the focus. “We need a larger number, a larger percentage of our populace, on board when it comes to being able to talk […] truth to power.”

Getty Images

Getty Images

But he argues there are real dangers for governments that stifle the voices of those who have legitimate concerns. “If a government is arrogant enough not to listen to people protesting and they have good grounds for protest […] there are bound to be those people who say we are going to escalate the protest.”

He helped organise last year’s Restore Nature Now march which brought tens of thousands of people onto the streets and was supported by a whole range of nature focused organisations including big charities like the National Trust and RSPB, as well as campaign groups like JSO.

Packham was hoping that by getting a whole range of activists together on a single stage “they would all see the bigger picture and recognise that there are far more commonalities between them than differences.”

But peaceful climate action does not get the same attention as non-peaceful action. “We put between 70,000 and 80,000 people on the streets of London, but because it was a peaceful demonstration made up of kids in fancy dress we didn’t get any coverage,” says Packham.

It is in this context that Ms Lunnon of JSO believes new forms of disruptive protest will emerge in time. “The movement is there and will find new ways to confront the government,” she says. “Nobody is shutting up shop and calling it a day. We know morally that we have to continue.”

However it is clear that, for now at least, the model that made JSO so notorious is dead.

Top picture credit: Getty Images

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You can send us your feedback on the InDepth section by clicking on the button below.